Ernest Thesiger’s

Military Service

Private Ernest Thesiger, Service #2546, of the Queen Victoria’s Rifles, 9th Battalion, London Regiment. Photo: The University of Bristol Theatre Collection/ArenaPAL

“I thought a kilt would suit me, so I applied at the London Scottish Headquarters, but my Scottish accent, assumed for the occasion, was apparently not convincing, and I was referred to another London regiment. Getting into a taxi, I consulted the list of recruiting stations and found myself in a queue outside the Headquarters of the Queen Victoria Rifles in Davies Street. I came away a few hours later a private in His Majesty’s Army.”

Ernest Thesiger, Practically True

Movements of the Queen Victoria's Rifles during Ernest’s tour of duty:

August 1914: Headquartered at 56 Davies Street. Part of 3rd London Brigade, 1st London Division. Moved on mobilization to Bullswater, then in September to Crowborough.

November 5, 1914: Left Division and landed at Le Havre.

November 27, 1914: Came under command of 13th Brigade in 5th Division.

“Arriving in the reserve trenches on the 31st of December, we found that all the dug-outs were knee-deep in water, so we set to work to dig others - but it was like digging on the seashore, each shovelful of earth we took out was replaced by a bucketful of water. Luckily there was a deserted and partially ruined barn on a line with our trenches, and we were sent there to rest, after receiving strict injunctions not to make any noise or show any light. Making a deep nest in the straw that nearly filled the barn, I slept until daybreak. I was sharing my breakfast and the remains of my Christmas chocolate with my neighbour when we heard a noise like that of an approaching express train, and a shell exploded on the roof, ripping off all the tiles which fell with a clatter on to those who were sleeping in that half of the barn. As our habitation seemed none too healthy, we began to make arrangements for a speedy move, but a sergeant at the door ordered us to stay where we were. Then again came that ominous rushing noise, and I crouched into my bed of straw knowing that death was coming towards us. There followed a deafening crash and then darkness.

There is a scene in L’Aiglon where the ghosts of Wagram are heard calling out ‘My leg!’ ‘My arm!’ ‘My head!’ and that is the scene to which I awoke. All around me my friends were groaning and telling the world of the wounds they had received. I realized that I was not dead, though I didn’t think I could move, numbed and bruised as I was by the tiles and rafters that had fallen upon me. Then my eyes fell upon my hands. They were covered with blood and swollen to the size of plum-puddings. My fingers were hanging in the oddest way, and I guessed that most of them were broken. I managed to stagger to my feet, wondering as I did so whether my breakfast companion had escaped before the explosion. I couldn’t see him, but he had left his boots behind, and knowing that next to his rifle a soldier values his boots, I decided to take them to him. But how? I couldn’t use my hands. Perhaps, I thought, I could lift them in my teeth. Still rather shaky on my legs, I stooped down carefully and then saw that in each boot a few inches of leg still remained. That was all there was of him with whom a few moments before I had been eating chocolate. Without looking round - I had seen enough - I made my way out of that charnel-house, leaving the bodies of twelve of my friends behind, while thirty others had been wounded. An officer outside told me to find my way to the dressing-station, and holding my hands above my head for fear that if I stumbled they would get more damaged, I walked back to a farm where I could get bandaged up. I looked at my hands from time to time to assure myself that all my fingers were still there - I could feel nothing - but was convinced that I would never be able to use them again. At the dressing-station a liberal application of iodine effectually did away with the numbness that had so far come to my rescue, and I fainted with the pain. Forty-eight hours afterwards I was in hospital at Le Treport, and three weeks later in England.”

Ernest Thesiger, Practically True

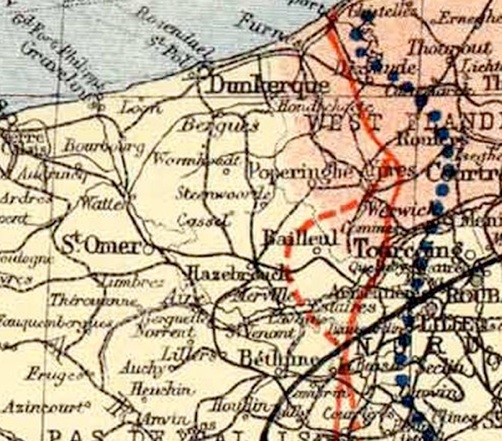

Map of the Western Front. Ernest was stationed near the town of Bailleul. British entrenched position is indicated by red line.

“Mr. Ernest Thesiger, a comedian of distinct ability, who originally made his theatrical name on the amateur stage, was perhaps the first actor to enlist in the early days of the war. He subsequently got a commission, and went to the front in September last. He served gallantly and well, and was wounded while in the trenches at the latter part of the year. Terrible rumours as to his injuries were told on all sides, and it was reported ‘on the best authority’ that he had lost the use of both his hands, and that one of his legs had been permanently crippled by the bursting of a shell. As a matter of fact, Mr. Thesiger is now in London and out of hospital. He received a very serious wound in his left arm and hand, but his right hand seems in thoroughly good working order, and his legs look still a well-matched pair.”

The Standard, February 3, 1915

Ernest was awarded the following medals on August 8, 1920:

The 1914 Star

The British War Medal

The Allied Victory Medal

The Silver War Badge

During his convalescence, Ernest devised a scheme for teaching other wounded veterans needlework, which eventually became the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry.