Ernest Thesiger

and the

Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry

“The problem of work for disabled soldiers is always exercising the minds of people; and thanks to a variety of efforts, suitable employment has been found for many men whose wounds seemed at first likely to prove a permanent barrier to their usefulness. Even the blind and the limbless have been found occupation and trade.

But there still remains a large number of men who, though in many cases unwounded, are none the less totally disabled. Bad cases of ‘Gas,’ resulting in injured hearts and weak lungs; shell-shocked men, who cannot leave their own homes; and others subject to epilepsy - all these men, in most cases confined to their houses - have to be given employment, if only to occupy their minds.

Three years ago in visiting hospitals, I was struck with the interest which invalids took in needlework and the skill they evinced in working their own rather crude designs. I offered to supply them with something a little more decorative in the way of patterns; but while they were still in hospital found that they were not easily interested in anything apart from their own artistic efforts.

I kept in touch with some of the needleworkers I had come across, and made the acquaintance of others who might be suitable for my scheme. I pointed out to them that if they worked the design with which I had provided them, their work when finished would be saleable. Once back among men who were earning a living the question of commercial value asserted itself. Thus induced they tried their first piece of serious work. Very seldom did they even to pretend to admire the designs provided for them, but when it was finished confessed that it ‘didn’t look half bad.’ I borrowed other pieces of old work to show them, and found that their taste was far easier to guide than would have been expected.

“Work for the Totally-Disabled” by Ernest Thesiger, War Pensions Gazette, May 1920

The kind of pattern that I gave them was the old cross-stitch chair-seat that was most beautifully produced in the 18th century, and which is quite different in design, colour and spirit from the ‘Berlin wool-work’ of the Victorian era. These exquisite examples are often to be found adorning a Queen Anne or Chippendale chair, though their life of two hundred years is in many cases nearly over. The chairs themselves have outlived their covers, and have now to be refitted with modern reproductions. The chairs, too, are being widely copied, and these replicas are often covered with modern pieces of work copied from old designs. This accounts for the large demand there is at present for this kind of work. Dealers have told me that the supply is not nearly equal to the demand.

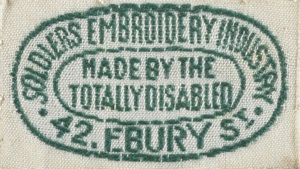

I tried for some time to get this industry taken up officially, but for some reason or another it was not greatly encouraged. About eighteen months ago as the result of consultations with others interested in teaching embroidery to disabled men an amalgamation was adopted, and ‘The Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry’ was founded. Already we have about a hundred men working for us.

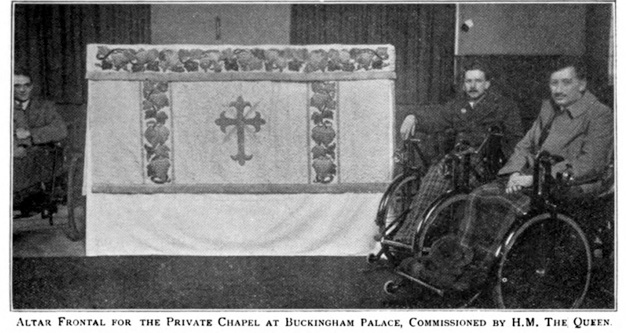

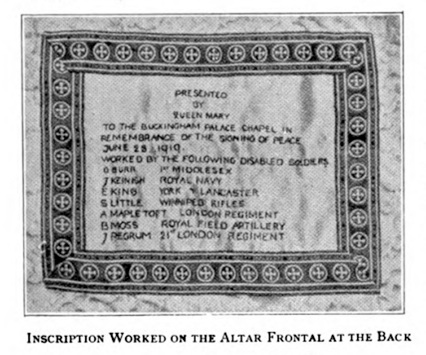

Furniture is not our only line. Some of the pupils show a marked aptitude for church embroidery, and the altar frontal in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace, which was commissioned by the Queen last year, is a fine example of their skill. For this branch expert modern designers are employed, but in the cross-stitch department only antique patterns are used, and we have been fortunate enough to borrow some fine examples from private collectors.

Although this is a work that any man might be happy to do, we only take full-pension men as pupils, those in fact for whom any other work would prove too strenuous. They work in their own homes and in their own time, and instructors are sent to them at regular intervals. A man’s earnings average at about 10s. a week, as most of our apprentices are not strong enough to work more than a very short time a day. But this is a useful addition, and the work itself affords so much interest that it has a marked effect upon a man’s health.

Infectious cases and cases of skin disease are not taken as pupils for obvious reasons. Any man either in town or country who wishes to take up this work can apply to the Hon. Sec. Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, 42, Ebury Street, London, S. W. 1, when he will be promptly communicated with and given a preliminary lesson. All work is paid for upon completion, the cost of materials alone being deducted.”

“On Tuesday the Prince of Wales will perform one of the kindly acts we have learned to expect of him, going to Chelsea House to view privately the embroideries executed by the disabled soldiers under the aegis of ‘The Friends of the Poor.’ This embroidery industry was started among ‘fighting men broken in our wars’ while they lay in hospital, and is being carried on by many of them in the War Seals Foundation Homes and in their own homes. Sir Owen and Lady Philiipps are kindly allowing an exhibition of their work to be held at Chelsea House, and invitations have been issued for a general show on the day following the Prince’s visit. The work executed by these crippled and paralyzed men in the woolwork section, of which Mr. Ernest Thesiger is instructor, is for the most part the copying and adaptation of antique designs in gros-point and petit-point, and orders are gladly received for chair seats to complete existing sets and similar work. The Queen of Spain has had a cover for a tabouret stool made for her, and Princess Marie Louise, the President of ‘The Friends of the Poor,’ a stool cover in petit-point in a Stuart design. Church work is also undertaken by the workers of the embroidery industry, and an altar frontal for Buckingham Palace has recently been executed. Work by which a totally disabled many may earn a livelihood and. which is more, sustain his own interest in life and pride of craftsmanship is hard to find. The embroidery industry offers a singularly happy opportunity, and the usefulness and beauty of the men’s handiwork would commend it even were their unforgettable claim upon their fellow-subjects of the Crown left out of consideration. Lady Philipps and Miss Anne Tennant are the Hon. Secretaries of the Industry, and enquiries should be addresses to them at 40-42, Ebury Street, S.W. 1.”

“Disabled Men Who Help Themselves” Country Life, June 18, 1921

Design worked by the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, Weldon’s Antique Tapestry Magazine, c. 1920.

“Mr. Ernest Thesiger, speaking at the thirtieth annual meeting of the Friends of the Poor in London yesterday, stated that a group of disabled ex-Service men had been commissioned to make all the vestment sets for the Roman Catholic chapel in the new liner Queen Mary. These ex-Service men (who are employed by the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, a branch of the Friends of the Poor) had also been given the order for the Haig banner for the Ypres Memorial Chapel. Princess Marie Louise, president of the Friends of the Poor, who presided, spoke of the value of the society’s work in helping to bridge the gap between the poor and those who wished to help them, but who were lacking in the necessary knowledge and experience. She described the sufferings of many elderly gentle people who, through no fault of their own, found themselves with barely enough to live upon. Lord Sankey emphasized the value of the society in the way in which it co-operated with the public bodies in getting assistance.”

“Vestments for Chapel in the Queen Mary” The Daily Gleaner, December 6, 1935

Quilt worked by the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, 166 x 233 cm.

Pincushion worked by the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry.