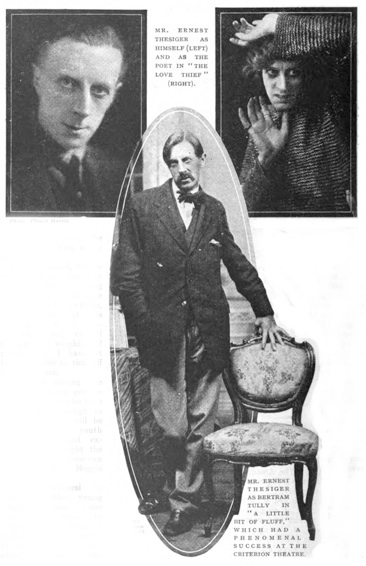

Ernest Thesiger

The Actor

“I hope that Mr. Ernest Thesiger will not mind being included among the six stars of tomorrow; I know, of course, that he has played leading parts in London productions - in ‘A Little Bit of Fluff,’ for example, but I want to include him because I believe he is going to make a much bigger name than he has made so far. I do not look upon him as one of those actors who can only get to a moderately good point and no further. To my mind, Ernest Thesiger is an actor to take a place as one of London’s leading comedians in years to come....Thesiger has the gift of being extremely amusing in a quiet, serious way. You may remember him as a delicious, pawky Scots gillie, in Barrie’s ‘Mary Rose” - a young man unexpectedly found to be full of university learning; and perhaps also, as a poet whose brains were his only weapon against two huge bally-ragging fellows in Mr. McKinnel’s production of ‘The Love Thief.’ His style is quite distinctive, and his range of character work by no means all of one order. For example, he was Captain Hook in ‘Peter Pan’ this year.”

“It would be impossible to deny Ernest Thesiger’s versatility. It is astonishing what, with his so pronounced personality, he is able to do. He made his name after returning wounded from the front in the early years of the war, in a ridiculous and imbecile farce, ‘A Little Bit of Fluff.’ He played this, I believe, for more than two years, which would have been quite enough, one would fancy, to destroy anybody’s talent, and then he startled us with his admirable tenderness in the part of the Scotchman in Barrie’s ‘Mary Rose.’ He was less well suited in Maugham’s ‘Circle.’ He again becomes most notable in Galsworthy’s ‘Pigeon’ at the Court Theatre. He had there a most difficult part, not quite realized, I think, by the author, certainly not quite given to us completely in earlier representations of it, and he put that final touch to it, as the artist should, and made it a convincing thing. His appearance is bizarre, and there are, of course, many parts in which he could not be well suited, but his intelligence is acute and he has an astonishing gift of adding poetry to all that he has to do. Even the most futile farce becomes something a little better when he touches it. I should like to see him play Iago and Richard the Third and the Fool in ‘King Lear’ and many other things. He is old enough and wise enough to know just what he is about; he is talented in all sorts of ways; a painter of no mean repute, an admirable musician, one of the best mimics London has ever seen, and finally, he is unlike anyone else at all. He has certainly a great future.”

“The Versatile Thesiger” Hugh Walpole, Vanity Fair, August 1922

“Rising Stars” The London Magazine

v 48, 1922

“‘I have played in nine films,’ said Ernest Thesiger, ‘and I am very cross about it.’

Should I meet a man who knows all about Eisenstein’s [sic] theory of relativity I regret to record that I would not be deeply moved, the reason being (so arrogant are men) that I know relatively nothing about Eisenstein; but as we have all tried to act (those screaming family charades) I could not resist a feeling of intimidation for one whose work is so assured.

‘There’s no organization in British films,’ Mr. Thesiger continued brusquely as though he had just discovered this alarming fact. ‘Every minute of my life is organized, so I begrudge the idle hours of sitting around the set.’

Now, I remember reading, in his book of memoirs, that Mr. Thesiger has a habit of electrifying his fellow travelers by taking out his crochet work in railway carriages; so, I could not refrain from saying, in a small voice, ‘Why didn’t you take your crochet work with you?’

‘But I always worked on the set,’ he declared without a blush.

‘What did they say?’ I demanded excitedly.

‘Unprintable,’ he sighed.

‘Please, please tell me,’ I begged.

‘--------------,’ he answered.

‘Unprintable,’ I agreed.

Cursing to myself the laws of censorship I let my eyes fall on the bowls of rose leaves and gentle watercolours which E.T. used to exhibit in Bond Street before he became an actor. Soothed by the delightful calm of the room, I began to forget my mission; Mr. Thesiger, however, had organized his day and he went on being interviewed whether I listened or not.

‘Always,’ he declared crisply, ‘I put the stage first. On the stage I can play the part of a young boy; by sheer personal magnetism I can make the audience accept me in such a role. The cinema, on the other hand, is a visual-aural and not a mental entertainment. Directors? Of course, they do everything in the films; copying out passages from great authors does not make one a writer, you see what I mean?’

But my time on the schedule was up and I could not tell him what I saw.”

Oswell Blakeston, Close Up, July-December, 1930