Ernest Thesiger’s

Spirituality

Ernest was a lifelong member of Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Street, London, where he frequently served as an usher and where he also sometimes read the lesson. His Christian faith was exemplified by his constant charitable activity, which included spearheading the creation of the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry.

“I make no claim to second sight, but there are days when I am certainly clairvoyant, and certain people become, as it were, completely transparent to me; when I am once attuned to them there seems to be nothing about them that I cannot read...This faculty of reading the past in people’s faces seems to come in bouts, and one year I was very much subject to it, so much so that I acquired a certain reputation as a wizard. The consequence was that people were constantly saying to me ‘Do tell me something about myself,’ and got quite annoyed if I couldn’t. I can’t always tell anything the moment I look at a person, but I always know whether I shall be able to read anything about them or not.”

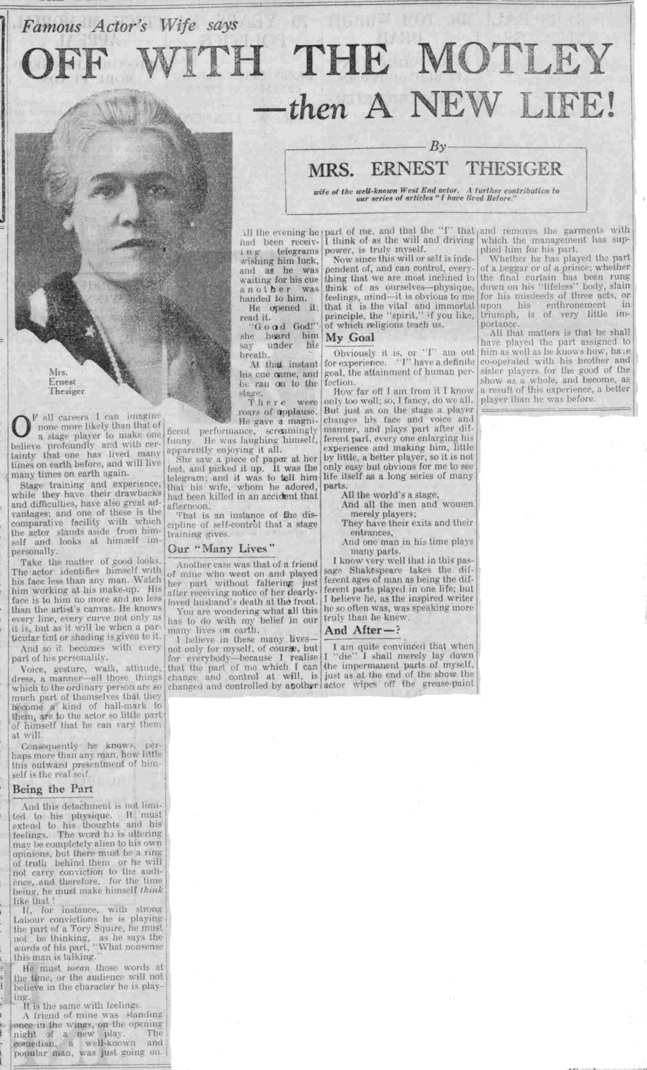

Ernest may have been a Theosophist, as was Janette. The following article by Janette expresses some of the ideas of Theosophy.

View of Sloane Square and Holy Trinity Church, c. 1905.

Ernest Thesiger, Practically True

“Out of a tray of lovely pendants I picked one, which I most admired. ‘That will cost you £3,’ she said. Surprised at finding it so cheap I said that I would buy it, but when she came to enter my purchase into a book she found that she had made a mistake and that the price was £30 and not £3. So I had sadly to give up any thought of possessing it. But I was reckoning without the charming saleswoman. ‘You have bought it for £3,’ she insisted ’and you must have it for £3.’ In vain I protested - it is the law she told me, and nothing that I could say made the least difference. I must have it. And have it I did. ‘It will bring me luck I know,’ I said and hung it round my neck.

When I got home there was only one, not very interesting-looking letter awaiting me. Suspecting a bill I opened it reluctantly, but the contents of the letter were quite unexpected - almost unbelievable. It was from a lawyer who wrote that he had been instructed by a client to enclose a cheque for £50 on condition that I didn’t ask where it came from. In vain I racked my brains to think of anyone who could have wished to make me a present in this way, and when I wrote to acknowledge the cheque begged that I might be told the name of my anonymous benefactor - but to this I got no answer and to this day I cannot even hazard a guess as to their identity.

After that I always wore the pendant on a piece of black ribbon and felt that it was indeed a mascot. One day a young actor of my acquaintance wrote and asked me to lunch at his club to celebrate his having got his first London engagement. But when he greeted me he looked far from cheerful and I sensed that something had gone wrong. During lunch I made him tell me why he seemed so glum and he confessed that not feeling very well he had been tested by his doctor who told him that he couldn’t possibly winter in England and recommended South Africa, ‘How can I possibly afford to go to South Africa,’ he moaned. ‘And how can I afford to give up my London offer?’ I handed him my jade and told him to hold it in both hands. As he did so a club page came in and told my host that he was wanted on the telephone. When he came back from the call-box my friend looked even more strange - not exactly happy, but completely bewildered. ‘That was so-and-so,’ he stammered, ‘offering me a part in a tour to South Africa.’

Whenever anyone I knew was depressed or out of sorts I made them take my jade and wish on it, and time after time it continued to bring luck.”

Ernest Thesiger, from his unpublished memoir, I Was.

“It was about that time that I was told by Teresina, the palmist, that I should have two other professions, and that my first change would be in 1909, several years ahead. I did not attach very much importance to her prophecy, though I did make a note of the date, but continued to consider myself a professional painter, and gave two moderately successful ‘one-man shows,’ at each of which I sold about £300 worth of sketches. But by the time that the fateful year of 1909 had arrived I had come to the conclusion that I should never make a fortune with my brush, and, just as I was feeling rather doubtful about the future, one of my own family, whom I always imagined to be seriously prejudiced against the stage as a profession, said to me, ‘I have often wondered why you never thought of becoming an actor.’

Encouraged by this suggestion, and the predictions of a second palmist, I began to ask myself whether such a course would be possible and what steps I should take if I should consider the proposal.”

Derby Daily Telegraph, February 8, 1930

Ernest Thesiger, Practically True